LITTLE ROCK, Ark. — So, often we hear about the problem of addiction. How it tears apart families, relationships and often results in incarceration or, ultimately, death.

But what is the solution? How do we save those who are struggling before it is too late?

The Exodus Project is dedicated to helping those who are incarcerated start a new life. Through family reunification, education, case management, this 12-week program for young men and women struggling with their addiction helps prepare them for release as they transition back into the community.

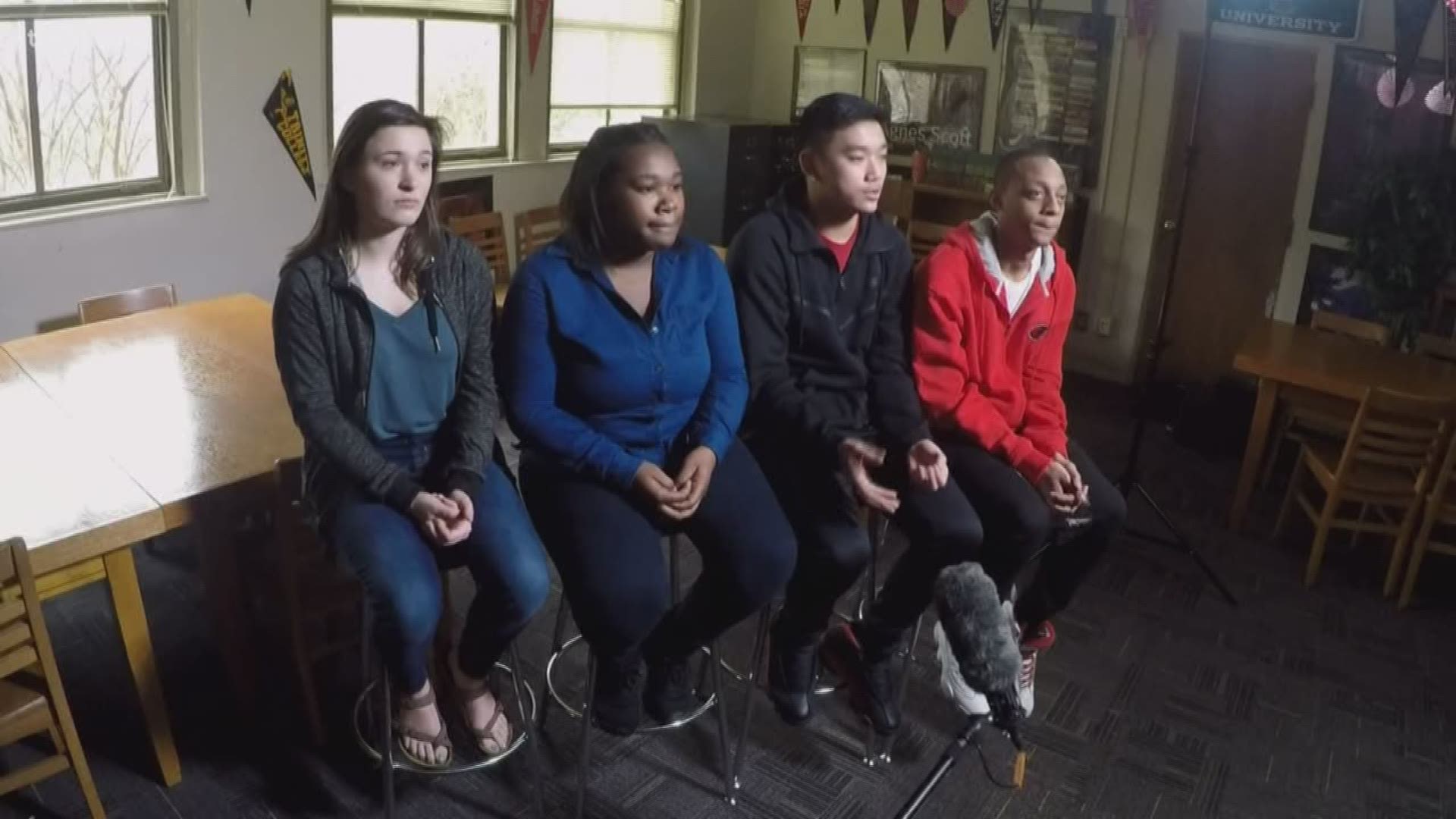

THV11’s Laura Monteverdi and photojournalist Breandan Conyers documented the lives of four young men in the program. Saving a Generation: Out for Life gives a glimpse into the lives of these men as they work to take back their lives from the strongholds of addiction and prepare for life after prison.

Chapter 1 - Journey to Exodus

In Arkansas, the recidivism rate is hovering around 56 percent. “We have about 200,000 Arkansans imprisoned right now. And interestingly, there will probably be around 10,000 released in the coming year and probably around 11,000 arrested and put back into prison,” said Paul Stevens, Executive Director of The Exodus Project. The cycle is unsustainable. And it’s costing us a fortune.

With the recidivism rate at 56 percent that means that once you are incarcerated you are more likely to go back to prison then you are to stay free.

“While there are many of those inmates who are in prison, I’m glad they are in prison,” said Stevens. “There are a whole lot more who are there as a result of the war on drugs and issue of substance use in America.”

A life at Arkansas Community Corrections isn’t peaches and cream.

Especially for 36-year-old Josh Walker. He is from Stuttgart, Arkansas, a father of two little girls, a farmer. His family owns a farm. “My whole life I’ve been working,” said Josh. “I always liked to party, went to school up in Fayetteville. I didn’t finish college because I was partying, and I knew I had a farm to fall back on.”

And that’s when it all started for Josh. He came back from college, got hurt and got on the pills. Josh got hurt in a combine accident and was prescribed opiates, but not long after that is when he began abusing drugs.

“I realized I was addicted when one morning as soon as my feet hit the floor, I snuck in the bathroom in my house and crushed two Roxy 30’s down on the back of the toilet,” explained Josh. And he’d do this with his kids and wife asleep in the next room just, so he could get his day started or it wouldn’t have happened.

“Next thing I know I’m sneaking out at night after I put my girls to bed and drive all the way from Stuttgart, to Little Rock to get pills. And then drive back as fast as I can knowing I have to work in the morning,” said Josh. He’d try to sneak into bed with his wife when he got back so she wouldn’t know that he had even left. “It got to where my wife left, I sold my house. I’m losing everything. It’s spiraling out of control,” said Josh regretfully. That’s when he started using heroin because it was cheaper, and he was starting to run out of money. “My parents wouldn’t give me anymore. And I wasn’t working anymore so I started stealing things. And that’s not me. I can’t even believe the things I was capable of,” he added. “The thing about opiates people don’t understand is like, nobody starts off saying, ‘I want to be a junkie, or I want to be an addict,’” said Josh.

Josh remembers in 2015 being on THV11 and other local news stations because he stole a grain cart. He was on the run. After a weeks long manhunt he was arrested. Josh was sentenced to six years in prison. “I was such a good guy, you know? And then it just went downhill,” he said.

During this interview with Josh he told us how his little brother had recently overdosed on heroin. He was four blocks from the prison in a chem free house.

“There’s no way to describe it, to not be there for my little brother,” he said. “Not even the point of right now – it’s before. When I could have gotten my life together. I could have been a better role model. I could have been a beacon of life for him to not settle.”

With addiction, you talk a big game. You promise so many things. But you never actually follow through. “And I promised my little girls so many things and it never happened so I’m tired of breaking their hearts,” he said.

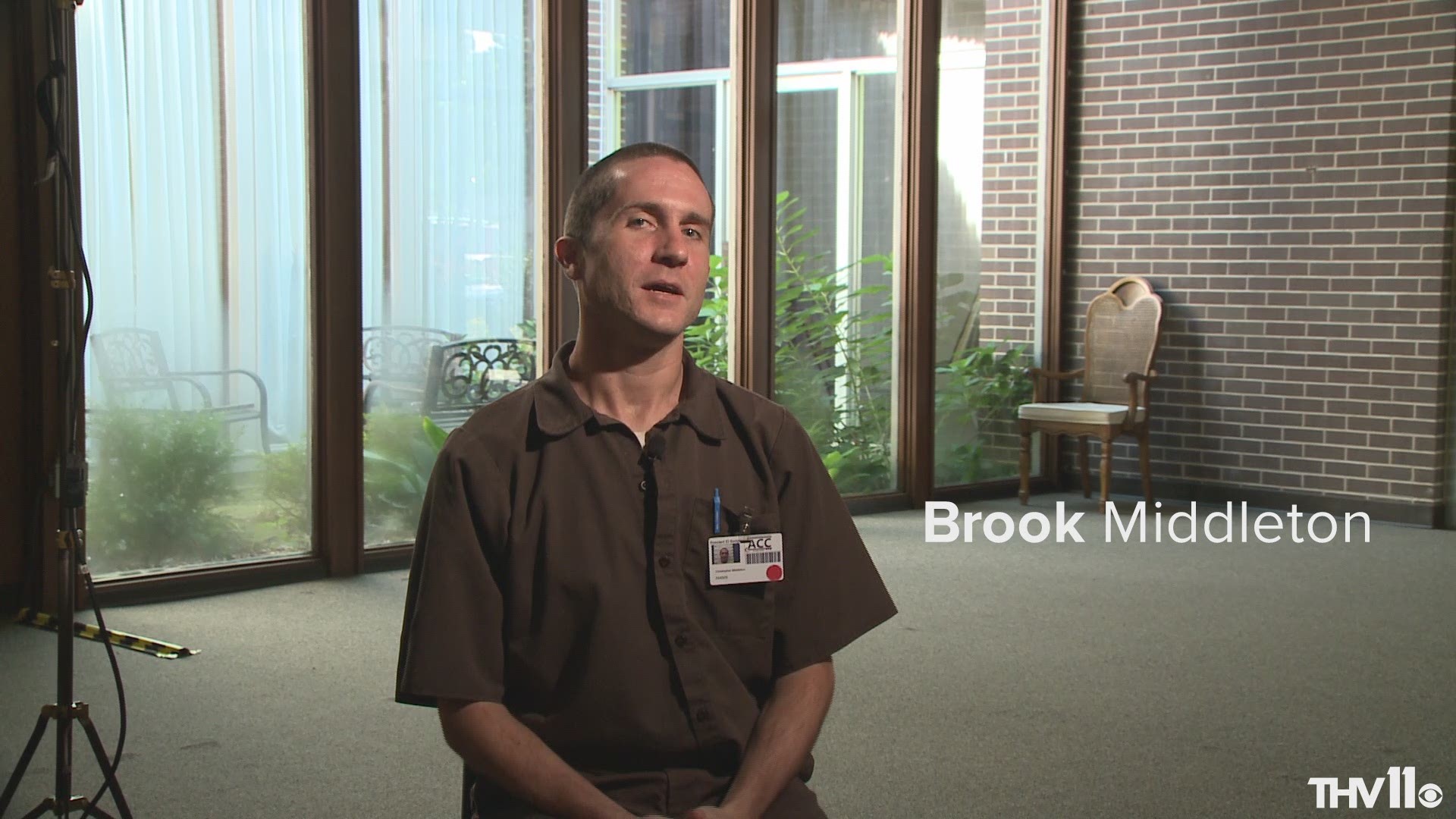

Meet 29-year-old Brook Middleton from Conway, Arkansas. Brook had a typical childhood, he grew up in a middle-class family. He played in the orchestra.

“So, I was like a band geek, you know?” he said.

He was a member of the French club. “Really it was the childhood most people would fantasize about having,” he added.

Brook started using alcohol at the age of 14, socially. He didn’t have a problem with it. “As I got older though, I started partying and started working at restaurants and bars and the drinking became a little heavier,” said Brook. At age 20, he started experimenting with harder drugs. Cocaine was the first, but the availability wasn’t always the best and then it progressed to meth. “I remember one night I went to a friend’s house and I saw him shooting up prescription painkillers and I tried it and from then on I was hooked,” he said. Brook expressed to us that the first time he tried it, he thought to himself, “This is probably what is going to kill me.”

But he couldn’t stop. “It was kind of insanity – we know someone is dying from it. Let’s go get some. That was our mentality,” he said.

Brook rarely visited the bar anymore and it just became a daily thing. His drug of choice is prescription painkillers. “Heroin was kind of my second drug. If I couldn’t find what I wanted I would go to heroin.”

At first, he said it didn’t change a lot. He was kind of living a double life. Brook would go to work and participate with his family and all the normal things. “By night, I would be like this drug addict,” he said. It took a while before Brook’s life really started to become unmanageable. “My upbringing didn’t show me how people really can be especially when drugs are involved. The lifestyles involved I didn’t understand that at this point,” said Brook. He can probably list the drugs he didn’t use faster than the ones he did use.

“I was arrested by the grace of God. At this point I had been toying with the idea of getting clean. And my life had become unmanageable,” he said. “I was completely homeless. I had quit my job. I really had like lost most of my friends and I had decided I was going to get clean.”

Brook was arrested after police found drug paraphernalia on him, some of the paraphernalia had residue. He was sentenced to six months in prison.

Stevens says he thinks we have thousands of nonviolent offenders who have offended who deserve to be penalized but we are doing it in a way that doesn’t help them and costs us a lot of money. “The question is what can we do different? How can we approach all that differently?” said Stevens. The Exodus Project’s goal is to help them to become equipped to do things they need to do to be restored to their families when they get out and get ready to go home.

The Exodus Project has an educational experience of 240 classroom hours. 12 weeks. 20 hours a week. At the campus we met these met at, they had to be bused in from the central Arkansas community corrections unit in Little Rock. The bus came every day at 8 a.m. until noon. For four hours the staff is approaching the inmates with an attitude of respect.

“The classes we do are designed to focus on changing mindset. They are typically on different things. And so, we have classes on entrepreneurship. We have classes designed on mobilizing your personal resources. How to make a plan and how to execute the plan. We have classes on manhood and parenting,” said Stevens. “There are a lot of problems that we face as a society that are bigger than we are. This is one of them. This is a problem where we are going to be better if we work together.”

Chapter 2 - Ms. Kathy “From healing to hope”

“Tell me this, guys. How many of you want, genuinely want to stay clean?” said Kathy McConnell. She’s an instructor at the Exodus Project. One of the inmates responded, “I’m for sure. I’m done with that life.” Ms. Kathy follows with, “Here’s the deal. Why wouldn’t you do everything that you possibly can to make sure that possibly happens? Because you’re going to be down there, down a dirt road I imagine, down a paved road, down a gravel road. But you’re going to be where there is not a lot of support. It would be hard for us to scoop you up if anything went wrong.”

Ms. Kathy teaches the young men and women about recovery and re-entry. She said all of her friends thought she was crazy to put herself in “danger.” But she never knew what they were talking about. She has never felt threatened, it never even occurred to her to be afraid of these people. “I think anyone of these guys would do anything I asked them to. I always say have the best bodyguards in the world,” said Ms. Kathy.

She believes these men would tell us she’s straight forward, doesn’t put up with anything in class, means business and has their best interests at heart.

Brook likes Ms. Kathy. She reminds him of his mom. “She keeps it real. For us, I think that’s important because so much of our lives have been part of an illusion. Not being really based on reality so to have someone that gives us that dose of reality that we need that keeps it fun and interesting, I think that’s important,” said Brook. “I’ve learned a lot through her. Because how she talks about addiction and feels about addiction, it makes me realize what I put people through in my addiction.”

By being an instructor with the Exodus Project it helps Ms. Kathy heal. It helps her give back. Giving back is her 12-step work. By doing this for three years, it has healed a hole that she has inside.

Kathy’s son is 32 years old. He’s been using since he was about 14 years old. “I spent many years in a very dark space. I spend the first few years in denial,” she said. Then she spent many years fixing him. “I had to get right with myself and understand that I have no control over what that young man does. I love him,” she said. “But I have to love him well. Which means setting really good boundaries.”

But today, Kathy is able to live a completely full life. She’s worth having a good life that is apart and separate from what her son does. And the Exodus Project is the way she does that.

Now, we want you to meet 28-year-old Jeremy Hall.

Born in Memphis, Tennessee, Jeremy grew up in a drug infested neighborhood. “My mom was a crack cocaine addict. My dad was a crack cocaine addict,” he said.

Jeremy also grew up in a gang neighborhood. “I moved to Arkansas for a fresh start. My mom, she went to rehab, and my auntie got custody of me in 2004,” he said. At 14 years old, he came and moved to Sherwood and has been here ever since. His drug of choice was marijuana. He started selling because in his mind he always told himself he never wanted to be addicted to drugs. That’s why he was selling them. “I have an addictive lifestyle, so I’m addicted to selling drugs,” said Jeremy.

He also has a twin brother. In January 2014, his twin was in an automobile accident and died. “He ran into the back of an 18-wheeler on opiates,” said Jeremy. He guesses his twin took some bar pills and fell asleep behind the wheel or was texting and looked up and it was too late.

The death of his twin brother is when Jeremy felt he was at his lowest point. “I kind of felt it’s a void I was trying to fill,” he said. “We were like best friends before he died. And it just does something to you. I have a good way of covering it up but I’m still dealing with it day to day.” So, he started selling more drugs.

“I’ve always been addicted to the fast cars. Money. Clothes. Everything that comes with it because living paycheck to paycheck just isn’t enough sometimes. Especially when you don’t have a college background,” said Jeremy.

Jeremy was arrested for possession of a controlled substance, and possession of drug paraphernalia. “Possession of intent. I was getting caught with things like marijuana, pills, scales, large amounts of money.” He was sentenced on February 5 to five years in prison.

“When I was in the free world when I wasn’t incarcerated, I could run from things. I can distance myself from certain situations [and] certain people. I can’t do that now. I’m forced to live with different people with different addictions and all the things that come with it,” said Jeremy.

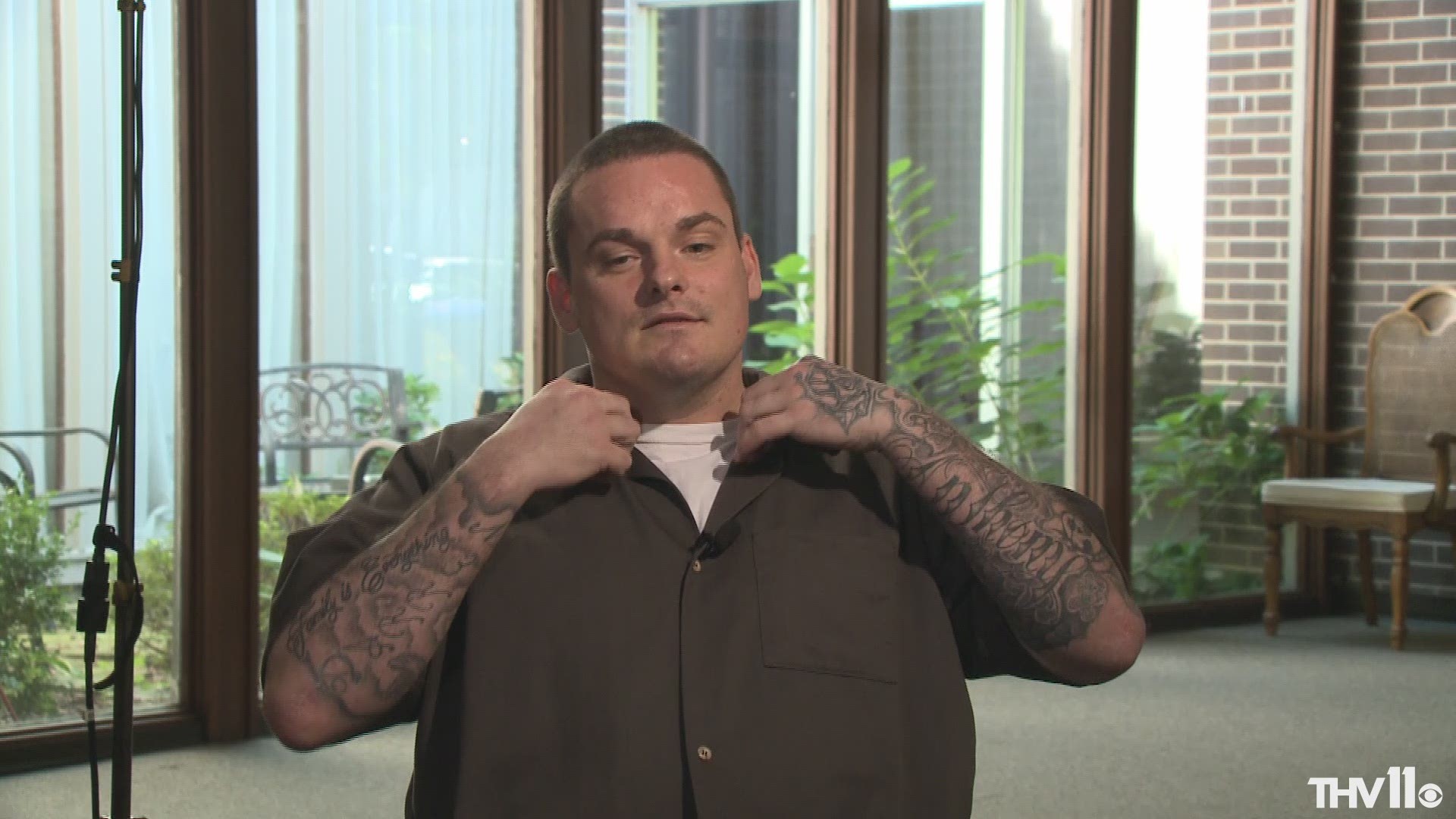

And finally, there’s 33-year-old Adam Nelson from Fort Smith, Arkansas.

“I can make everyone laugh. I like to joke around. Playful. Sometimes too much. I like to shine a little bit,” said Adam.

A funny guy. But the reason Adam is behind bars isn’t so funny.

Adam is in prison for his drug addiction. “I didn’t come from a broken home. I didn’t use drugs because something happened to me or I was treated bad as a kid. I had a good life,” he said. He started out smoking weed when he was a teenager, then it escalated to pain pills. Adam’s drug of choice?

Oxycodone.

It all started around age 22, so he’s had this addiction for over a decade. Adam’s life was positive. It was good as a kid. He had a good job. He was married for five years – in a relationship for 16 years with his high school sweetheart. They have three children together. “Looking back on it now it [was] just – a mess,” he said. It started with Oxycodone then he went to heroin and other stuff. He was using drugs in between as a crutch for that drug when he couldn’t find it. “Eventually let to starting to sell drugs to pay for my drug habit,” Adam told us.

But Adam’s wife and high school sweetheart had enough. “At 25, I lost everything. She stayed with me the first trip and she rode it out with me until about three years ago,” he said. Holly just got tired of worrying if Adam was going to kill himself.

“There’s a lot of incidents where I would leave and go get high. I wrecked my car in Oklahoma City, twice,” he said. OKC is where Adam did heroin for the first time. They had moved from Arkansas to start over and it was good, no drugs, for almost three years. And then one day Adam ran into a girl that had some.

“The first time I did heroin, I did it in an IV. And I remember we pulled in the parking lot, she fixed it. When I did it, I injected it and it took me to Cloud 9,” Adam said. “I look up and I was in the ambulance, they were screaming at me.” He described how he could hear their voices and could see a window behind them and see traffic moving to the side. And then he faded out. “I hear them hit my chest again and she’s yelling at me, ‘What did you take?’ And I said, ‘Heroin.’ And I went back out.” When he woke up again he was in the hospital and his wife was there with their 3-year-old son at the time. “And the look on her face, she was mortified,” he said.

He’s overdosed a couple times. There have been several incidents where he’s been found in cars passed out at gas stations. Adam once passed out at a stoplight after partying for a couple days in Fort Smith. “Drove back to OKC, went to the pharmacy, took a bunch of prescription pain pills. Fell asleep at the stoplight with my foot on the brake,” he said. “I could have let my foot off the brake, pulled into traffic and killed somebody.”

This is Adam’s third time in the Arkansas Department of Correction. His most recent arrest was he was sentenced to six years in prison.

“I know one thing is for sure, is if I don’t change now, time is running out. I might not have that much time to change anymore,” he said.

Ms. Kathy looks at these young men and she sees her son. Her son is not a bad guy. She tells them she doesn’t want to pick up the paper and read their name. “The reality is that in my heart I’m afraid this is what will happen to my son,” she said. “These are people. They can’t be judged by what they have done. These are human beings, and everyone deserves a second chance.”

Chapter 3 - Catfish “Tattoos and testimonies”

Stevens said that they’re not the ACC. They are not the state of Arkansas. They believe in these peoples’ potential and they believe in them because they’re our own.

In the first two to three weeks, they don’t really buy all that. They are just kind of wondering. But after the fourth week, it starts to sink into them that the Exodus Project is serious, and they’ve got lots of graduates coming out who are successful.

“Reality is, they are all pretty anxious and they are all unsure of what to expect. And so, they tend to be more closed. They tend to be more manipulative but then we just start. And pretty soon they find out that these are volunteers. We have no reason to be here other than for them,” said Stevens.

Another one of those volunteers is Catfish Jimmy. His real name is James Brassfield. He teaches the conquering chemical codependency class at the Exodus Project. When James was a kid, he used to go noodling in Oklahoma. James is from Tulsa, Oklahoma. Noodling is where you get in the water and stick your arm down in a hole and catch a catfish. His grandpa would always take him noodling. His uncle, who was successful, called James, “Catfish.” And his grandpa, who was successful, went by Jimmy. So, when James named his tattoo shop, he wanted to name it after successful people in his life, so he named it “Catfish Jimmy’s.”

But back in Oklahoma, James got into a lot of trouble. He was raised in drugs. He started using when he was 13 years old. Started selling when he was young. “Pretty much my whole life was involved in drugs and addiction,” he said.

But James didn’t want to be a tattoo artist if that’s not what God wanted him to be. “God said, ‘You are the perfect tool for me. You can go places where a lot of people can’t. You can reach people that a lot of people can’t reach.’ And I was like, ‘Okay.’ And he put it on my heart. And I was like I am going to use my tattoo shop for my testimony and my ministry as well.”

Less than two years after James got out of prison he learned about the Exodus Project. And he signed up to volunteer to teach a class. His class is a crash course, a 12-week program on the 12-step program. Its faith based. “I’m very comfortable with them. Like, I tell them I don’t speak above them. I don’t talk like I’m better than them. I’m one of them. I’m going through the steps with them. I’m going through the program with them,” said James. They share the same past, the same stories.

In one of the classes, James was telling the men, “Whether you were doing good for a while on parole and something came back and bit you in the butt. Whether you failed a drug test once or whether you got popped with something. Drugs were involved somehow. In destroying your life and separating you from the ones you love. So, you have a problem.” Josh thinks Catfish [James] is pretty cool. “He’s been through the ringer. And the fact that he’s been through it all and comes to give his testimony,” said Josh. “The dude is passionate about what he does. He is one of the guys who is giving me inspiration. He’s giving back and not getting anything out of it. Except what he gets in his heart for himself. Man, I dig it. I dig what he’s doing.”

“Everyone of your friends and family that are sober are not going to want anything to do with you. But that’s where God is pretty awesome. Because he restores those relationships,” James told his class.

Over the week’s James has seen them change. James has seen the look in their eyes change. He’s seen their actions change. He’s seen them become more involved in the classwork and in talking in the group discussions, he’s seen guys that don’t talk in the unit, don’t talk during class the first few weeks – they completely opened up and they are the ones that don’t stop talking. “Once they open up they break down those walls and those barriers and start working those steps. They change, and you can see the light just *snaps* ignite in them,” said James.

“A lot of times when you are at the bottom of the barrel you think nobody cares. And this place really shows them there are a lot of people who really care and want to see them do better in life and be a part of the community,” said Josh.

Brook added, “I want to make the world better. I want to help people. I want to share [the] love. And spread life amongst the world. Being here and getting to know myself, learning to love myself has allowed me to see other people who are where I used to be. And who haven’t learned to do that. That’s my wish, is for everyone to learn to love themselves like God has shown me to love myself. I really think that’s the whole issue with addiction is not understanding that.”

Chapter 4 – Finding freedom

“Do you think it’d be okay if I made a phone call?” Brook said as he walked down the hall of the prison. “Mom? Hey mom, how are you?” he said.

“I’m ready to come get ya’” said his mother.

“I’m ready for you to come get me, too,” he said.

“Are you nervous?” she asked.

“No, not at all. I feel great,” said Brook.

“Well, good. Good. Well, I’m getting ready to come. Gonna get a few of your things together so you’ll have some good clothes to wear out,” she said.

“Awesome,” replied Brook. “You know that is what I’ve been looking forward to the most is putting on my clothes. My normal clothes.”

This is the conversation Brook had on the day of his release. “Today, you know I’m kind of at a place of peace which is kind of a weird place for me,” Brook told us. “Being an addict, I feel like that’s the primary problem we have is that we have so much emotion and pain and thought and we don’t know what to do with it.”

Brook told us it just like swirls around inside them and it doesn’t have an outlet. “So, to be at a place of peace today is an awesome feeling. It’s very liberating,” he added.

We talked to Brook’s mother, Judy Summers. “Brook has never been this far before. Maybe he will do better this time. And its real hurtful sometimes to say I don’t think he’ll do better and sometimes I do feel like that.” It’s okay to feel doubt, and it’s okay to feel fear. These are common emotions from a loved one during times like this. “I don’t want to discourage him, and I don’t want him to think I don’t have hope in him or faith in him. But it is hard sometimes to say I think he’ll be okay,” said Judy.

This is life or death.

Judy hopes that Brook realizes that, and she hopes he realizes he has got to focus on himself. This is about Brook. This is not about helping someone else. “I hope he takes the time to see what he needs and gets a straight plan and tries to stay on plan. If he has a plan and can continue to focus on that, I think he can do it,” said Judy.

Let’s take you back to class now.

“You’ve got to take a risk. You’ve got to reach out of your comfort zone. Take a risk. Take a step forward,” said one of the Exodus Project instructors.

“I’m really just trying to squash my fears and face all of them. It was a fear for me, coming here. When I get out I’ll be incarcerated for almost a year, so I’m facing a fear just being here because I knew I had some time to do,” said Jeremy Hall. “But I didn’t know it was going to be a full year. But when I get out my fear is getting back adjusted to the world, getting back to working, taking care of my kids and just living life.”

Kim Maxwell is a second year, social work student at the University of Arkansas at Little Rock. She said Jeremy has been vocal, never had a problem letting people know who he is or what he plans to do. “But there has also been this loneliness to him. Having to move from Memphis to Arkansas, being away from your caregivers, mom and dad, and being here,” she said.

Growing up, Jeremy always felt alone. He said he could be in a room of 100 people and still feel alone because he didn’t feel like anyone understood him. He felt like an outcast. “He knows what he wants to do and what he needs to do with making amends with his family. And also giving back as well. Which is one of the most beautiful things that I hear him say is just how he wants to come back to Exodus,” said Kim. Jeremy wants to be a mentor.

“I don’t want this to be the last place I end up before I leave this world. I want to see the world. I want to go [to] some places. I want to do more stuff that I have been doing so to do that I need to do some stuff I never did before,” said Jeremy.

Josh Walker said if he had to stay in the prison building all day long he would go crazy. They wake you up every morning at 4. “You get hurdled around like cattle,” he said. “You gotta do what they say and when they say it. It makes you want to go home. And not come back here. To any place like this.”

We spoke to Josh’s family. “We were told one time that Josh was dead. About six months before our youngest son OD’d, they brought him back. But we had to – it was – we had to wait a couple of days to find Josh. Couldn’t find him,” said Kelly Bock, Josh’s mother. She said the one thing that shocked her was how big the problem really is. That people have no idea. “It’s a big deal. It’s a big deal,” said Gary Bock, Josh’s stepfather. “It took us down,” said Kelly. “People don’t understand, I know we didn’t. And I never will,” she added. “It can’t be put into words.” And Gary agreed.

Josh said, “I can’t tell you right now that if I was out or if there was some heroin or pills around me, that I wouldn’t do some. To be honest with myself and with you, its so scary. You don’t understand the power it holds over you.” Josh wants his little girls to be able to call him and he’s able to answer. “I want my mom and my dad to be able to say they are proud of me,” he said. “I’d love for them to just be able to smile for once.”

The only thing Josh hasn’t quit on since he started his addiction is drugs. He’s quit on his family, his friends, and any responsibility he’s had. But he says he’s not going to quit on this. “This is a big deal that I’ve finally come to terms with everything. And if this place can even give me a little chance to get any of my life back, I am going to do whatever it takes,” said Josh.

“Sometimes it takes coming to places like this to wake up and smell the coffee. We’re not only hurting ourselves, we’re hurting our kids and our family that depends on us. And everything else, man. We really all live as a society, we was just doing the wrong thing. Even the people who ain’t in yellow right now everybody makes mistakes. You know, it’s just about dusting yourself off and trying again,” said Jeremy.

Back to the hallway.

“What we’re going to do is take you to the crash gate. I’ll get you, your clothes from baby boomers and get changed out and about 10 o’clock I’ll call you out and you’ll be out the door,” said detention officer Chris McGraw.

“Sounds good to me,” said Brook.

“Alright, man,” added Chris.

“I am excited to rebuild these relationships I had with my family and my loved ones. I feel like that is such an important life that I have been missing out on due to my addiction, so I’m really blessed to be able to do that,” Brook told us right before he got out.

“14 delta, 9 echo, Charlie, I need Middleton. Resident Middleton in the crash gate with all his property.”

“There he is!” said Judy as she waits outside the jail door for Brook. “Oh my gosh! Freedom! How are you?”

“Hey!” said Brook as he kisses his mom.

“I’m so glad to see you!” said Judy. “You have clothes on! How are ya?”

“Good, how are you?” asked Brook.

“Good, honey! Awe. Doing okay today?” she asked her son.

“Yes! I don’t think there is any way I could be doing any better,” Brook said excitedly.

“Physically I found myself in prison. That’s what it took for me to figure out how mentally imprisoned I was. So, this experience has helped me to break those chains that I didn’t even know I was wearing for so long. Find freedom I have never know,” he told us.

Brook graduated from the Exodus Project in Term 28. Before the other three guys.

Chapter 5 – “I’ll be out for life”

Before graduation, we catch the guys going through some of their stuff as they prepare for the big day. “For a long time, I thought going out into the world, there was no hope. I had this weight on my shoulders for the longest time and I’ve learned through here, you’ve got to let that go,” said Adam. “There’s no reason for me to go back to the life I have been living.”

Adam said it’s a scary process. “If I sat up here in front of y’all and said I wasn’t scared that would be a lie,” he told us. “And that would definitely be a lie and that’s the thing that I have learned that its good to be scared. Because now I’m more aware. I know if I go back out there and I don’t take my life serious then I’m not going to have a life.”

Reflecting on what they’ve been through and what’s to come.

It’s graduation day. The inmates hug and greet their loved ones who have come to watch them.

“I missed you!” said Adam’s daughter as she hugged his neck.

“I missed you, too!” he responded.

So, how were the guys feeling? Well, we asked them.

“Today is graduation for Term 29 Exodus Project,” said Adam. “I feel good because I’ve accomplished so much that there is no reason to be nervous or sad. Just embrace it. I think my dads going to be here, that’s big for me. My girlfriend. My kids. My brother. They are coming out to support me.”

“You been good?” Jeremy asked his son as he picked him up for a hug. His son nodded his head in agreeance.

Jeremy told us, “I’m feeling excited. My kids are coming. I haven’t seen my kids in eight or nine months. So, I’m going to be excited to see them. I’m ready to talk and tell everybody the things the program has done for me.”

They begin with a prayer:

We thank you for this Exodus Project and the support team they’ve provided us with. We also thank you for the friendship you’ve allowed us to create through this Exodus program. We thank you for allowing our friends and family to be here with us today and we just ask for your blessing throughout this graduation and that we allow your will to be done. Amen.

Then the speeches begin. Each man presented how this program has changed their lives and what they hope to accomplish after finishing the Exodus Project.

Here is part of Adam’s speech:

See what I’m going to talk about is change. And the process and growth of change. See behind these doors, week by week, and month by month, after day by day, we peel back layers and we got to the core issues of what is really going on. And I found out that I had a lot of pain inside of me and I had to let that go. I chose to speak about change because change is something we all have to go through. It’s a process. It’s all growth. And it’s hard. There were tears shed in these rooms. You know you are getting into deep stuff when your teacher has to shut the door and say, ‘Look, everything that happens in this room, stays in this room’ But you’re not hiding a body, you’re crying. You’re grown men, crying. We’re real men with real issues. Real problems. And we’re coming up with real solutions. Can I get everyone to stand up for just a second? My Exodus brothers only. If you want to know what change looks like through the eyes of the Exodus Project, look at us. That’s all I’ve got to say.

Here is part of Jeremy’s speech:

I’ve been locked up since February 5. And when I get out, I’ll be out for life. This hasn’t been easy. But at the end of the day I can still smile in the face of adversity. We started with 12 guys and we ended with 12 guys. Teamwork makes the dreamwork. I’ve hurt a lot of people in my past and when I get out I’m gonna right my wrongs. God is still working on me and he isn’t done yet. I became teachable and I am not the same person as when I came in. I might not be where I want to be in life but I’m sure not where I used to be. Things happen for a reason and there’s reason for the season. It’s time to be out for life. It’s time to realize when I take things for granted, the things I’ve been granted with will be taken. It’s time for me to take full accountability of all my actions and stop blaming society and my childhood. The Exodus Project has taught me that I’m not the only one who has failed and needs help.

Here is part of Josh’s speech:

We worked really hard on this, guys. I’m nervous because this means a lot to us. This is hard for us to talk about. I’m here today to tell you about hope and what it means how Exodus helped me find it. Before I got here, everyone I cared about had gotten away from me because I was self-destructing. My ex-wife knows all about that. I had lost everything, including everyone I loved including my family. My mom, my dad were having problems. I mean, both of their sons were in jail, guys. Things have gotten dark. When you’re addicted, me and my brother both we put my parents through hell. I just want to tell them, I love you guys, man. I’ve been locked up for 18 months and I haven’t even talked to my best friend who is my ex-wife, in a long time. Or got to tell my two little girls how much I love em. But since I’ve been in Exodus my faith in God and myself and relationships have been restored. To my two little girls I have something to say. My dad killed himself when I was 16. And I told myself I would never do that to my kids. I would never do that. Guys, I killed myself with addiction. I turned my back on my kids. And I said I would never leave them like he left me. And I will spend the rest of my life trying to make it up to them. I know they’re not here but maybe they’ll get to see this one day. One night, laying in bed it was storming and my little girls wake up and they can’t see me, its dark and they said, ‘Daddy, are you there?’ And I said, ‘Yes baby, I’m here.’ And they said, ‘Daddy, is your face turned toward me?’ ‘Yes baby, my face is turned toward you.’ And they went back to sleep. Even though they can’t see me now, I just want them to know my face is still turned toward them. And I love them forever. Last guys, I’ve got to say I came to prison to find my freedom. I can’t give you what I have but I can tell you where to find it. Its at Exodus and out for life. Out for life doesn’t just mean out for the rest of our lives. It also means out to live life. To all my Exodus brothers, let’s get out for life. I love you guys, man.

The guys said they loved him to and then it was all applause. Each were awarded for their accomplishments in the Exodus Project.

Adam is holding onto his girlfriend and tells us, “I feel like we just won the championship game. That’s how I feel. If I can have champagne, I would. Nah, I’m just playing. I’m nonalcoholic these days.”

“I’m proud of you,” said Adam’s daughter.

“Thank you, baby!” he responded.

Josh felt like he had a lot to say to his mom, dad and ex-wife. But this was like a public apology and was more beneficial for him. He was able to get a lot off of his heart and feels better. “I’m actually starting to be able to forgive myself,” he said.

“The Exodus Project has really just showed me, don’t let your past define me. Yes, I come from a rough neighborhood in Memphis, Tennessee but that’s not where I’m at right now. That’s not where I’m trying to go, so I feel like, you know, I’m being the person that my brother wants me to be,” said Jeremy. Even though Jeremy came to jail where he needed to be, he feels like this didn’t do anything but mold him into the person that God intended for him to be.

“It’s a fight to get back out of it. It’s not even like a… I’ve been in fights. This is a war,” said Josh. “Things have changed and its all because of this place and I’m indebted for the rest of my life.”

The Exodus Project is a haven for greatness. It allowed these men to make some connections in their lives that they won’t take for granted. “This isn’t for anybody else. This is for Adam. And one time I had to learn that Adam had to be selfish. Because I’ve got a good heart. I like to do everything for everyone and impress everybody and all that. It was a selfish move to change myself, so I could change for my family. And change my life as a whole.” said Adam. “With that being said, Adam Nelson is out for life. Mic drop! I’m out!”

Where are they now?

Brook is living with his family in Conway and working two jobs. He earned enough money to buy his own car, and he’s hoping to soon begin classes to become a counselor.

Jeremy was released from jail in late January 2019. He’s living in Little Rock, where he works at a restaurant. And he’s currently enrolled at Shorter College.

Josh is serving out his sentence at Arkansas Community Correction in Little Rock. Once released, he plans to work full-time while attending a 12-step program. He also hopes to get involved with his church.

Adam is also serving out his sentence at Arkansas Community Correction in Little Rock. He hopes to one day become a peer recovery counselor and use his testimony to help others.