A couple of years ago, Lynn Sarmento of Greenville, South Carolina, called 911 to report a domestic disturbance.

She waited for an operator to pick up. And then waited some more.

“I stayed on the line for almost two minutes and no answer,” Sarmento says. “The guy ran off … as did the girl.”

When Americans dial 911 in an emergency, they expect a fast response and a reassuring voice at the other end of the line. But 911 centers across the country are struggling to hire enough operators, slowing the time it takes to answer calls. On rare occasions, the delays have led to injury and even death. While the crunch has been an issue for years, it has intensified over the past year or two as the nation’s low 3.9 percent unemployment rate increasingly spawns labor shortages across the economy.

That makes 911 dispatcher positions, which can be highly stressful, especially tough to fill.

“In any environment where you have increasing competition for workers, a worker is going to have more choices,” says Christopher Carver, operations director of 911 centers for the National Emergency Number Association (NENA), which promotes 911 awareness and advances. “People want to work in places they like. 911 centers can be challenging places to work.”

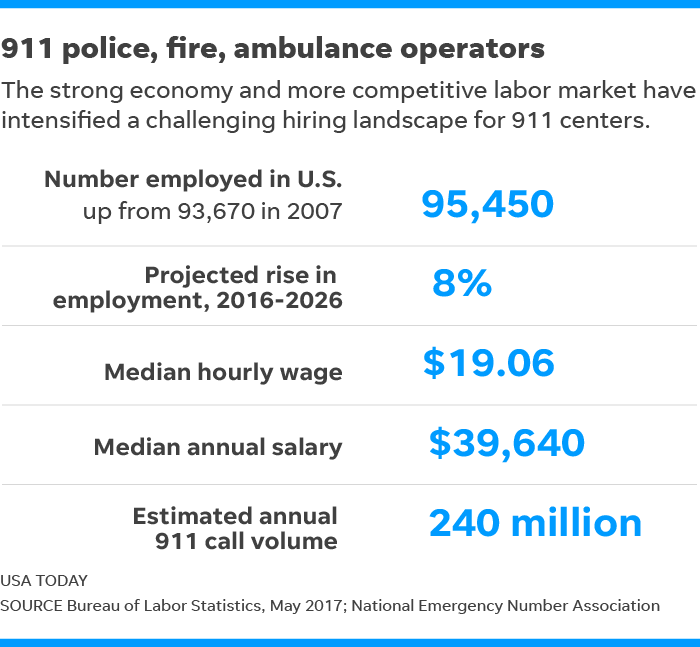

No one keeps national data on 911 operator shortages. But Carver says the gaps have worsened and spread – from larger cities to small and midsize ones as well – as the U.S. unemployment rate has fallen. Most 911 centers, he says, are short-staffed. Americans make about 240 million emergency and nonemergency 911 calls a year, NENA estimates.

'It's bad'

In Little Rock, Arkansas, the 911 communications center, which handles police and fire calls, has 11 openings among 68 positions, says Capt. Ty Tyrrell, who oversees the facility. So far this year, 66 percent of 911 calls have been answered in 10 seconds or less, substantially below the 90 percent standard set by NENA. Last year, 7,103, or 3 percent, of the 246,290 emergency calls took more than a minute to answer.

“It’s bad,” Tyrrell says. “When people call 911, they want it picked up on the first ring.”

Early last year, the 911 center did not answer dozens of calls from two people trying to report an attempted suicide. Four operators were on duty and received 108 calls in 20 minutes. The two callers kept hanging up and redialing, which repeatedly put them at the bottom of the queue. The person attempting suicide was found unconscious but survived.

Last year, Little Rock's 911 center received 608,825 calls, a 28 percent increase from 2010.

The strong economy and more competitive labor market have intensified an already challenging hiring landscape for 911 centers. Operators often talk to callers in the middle of crises who are scared, angry or disoriented, and they can’t afford to make a mistake. The pace is frenetic, and many operators work 12-hour shifts as well as a growing overtime load.

That creates a dispiriting cycle in which worker shortages lead to more overtime, making operators more stressed and fatigued – and more apt to make mistakes and leave the job. Last year, Little Rock hired 21 operators, but the same number quit.

“There is intense pressure to make rapid, high-pressure decisions,” such as prioritizing emergencies, NENA’s Carver says. “The portion of people who are really candidates is quite small.”

Job applicants typically undergo an aptitude test, background check and psychological evaluation, among other hurdles, that can take a few months in total. Before they’re certified to take calls on their own, operators are trained at an academy for at least several weeks, followed by six months of coaching at the 911 center.

Here's how a 911 call is handled: At most centers, call takers key information from callers into a computer for dispatchers, who decide which agency – police, fire or medical – and emergency official should respond. Over time, call takers are trained to handle dispatch as well, and many alternate between the roles.

In May 2017, there were 95,450 police, fire and emergency medical operators in the U.S., according to the Labor Department. They earned a median wage of $19.06 an hour, or $39,640 a year nationally.

To attract more candidates, Little Rock over the past two years has increased the starting salary of call takers by $6,500 to $35,000. Dispatcher starting pay has jumped $12,200 to $43,000.

But Tyrrell says the raises have helped only modestly. Many job applicants prefer to work in less busy and lower-paying – but also less stressful – centers in the region’s smaller towns, he says.

Many millennials, he says, similarly prefer slower-paced jobs even if the salaries are lower. “They’re much more casual,” he says. Record clerks, meter readers and secretaries are among the occupations whose median pay is roughly similar to 911 operators.

Tyrrell has taken the usual steps of running ads online and taking part in job fairs. Now, he plans to recruit college students majoring in criminal justice for part-time jobs answering nonemergency calls, easing the emergency call burden for full-time operators. The students would be candidates for law enforcement jobs after they graduate.

Cellphone calls swamp 911 centers

The spread of cellphones has exacerbated the 911 call logjam by often prompting dozens of bystander calls for a single traffic accident, Tyrrell says.

In Portland, Oregon, just 14 percent of 911 calls this year have been answered within the required 10 seconds. That’s partly because cellphone callers initially hear a recorded message.

The filter was implemented because a big share of cellphone calls are inadvertent pocket dials. Callers must press a button or make a sound to connect to an operator. The center recently updated the filter so that it’s activated only when there are too many calls for operators to handle.

That should significantly improve response times, says Bob Cozzie, director of the city’s bureau of emergency communications. Still, there are nine vacancies among the city’s 105 operator positions. And even when 12 recruits in training help fill those positions, the center would still need the city to provide funding for about 23 additional operators to meet NENA's call response standard, Cozzie says.

Many cities and counties, in fact, provide inadequate funding for 911 centers, and in some cases divert 911 funds for other uses, Carver says.

Slow response can lead to tragedy

In San Diego, hiring freezes sometimes prevented the 911 center from filling open positions. In 2016, there were 20 vacancies among 134 operator jobs. The understaffing led to tragedy that year when parents of a 3-day-old baby bitten by the family dog had to drive the boy to the hospital themselves after their 911 calls went unanswered. After staying on hold for 28 seconds without reaching an operator they hung up and dialed again, fruitlessly waiting another 34 seconds.The boy was pronounced dead at the hospital.

Since then, the city has allowed the 911 center to hire continually. Salaries were bumped up by 15 percent, and operators were given one-time $1,000 bonuses. There are currently just nine vacancies among the center’s 142 positions, says Roxanne Cahill, a police dispatch administrator. About 90 percent of calls have been answered within 10 seconds so far this year, up from 68 percent in 2016.

Many localities rely on overtime to cope with the worker shortages. The 911 center for York County in Pennsylvania has 60 operators and another 25 openings. Operators must work at least 12 hours of overtime a week and have racked up about $800,000 in overtime so far this year and more than $1 million each of the last three years, county spokesman Mark Walters says.

“We do tend to put our personal lives on the back-burner,” says Cheryl Cobb, 62, who has worked at the center 11 years and is logging about 20 hours of overtime a week. “If it’s between watching a TV show and getting more sleep,” Cobb opts for the latter so she’s more alert for her shift.

The job, she adds, is stressful. She sometimes juggles communications with as many as several dozen officers. And the center is so short-staffed that she often handles call- taking and dispatch duties at the same time.

The overtime can take a toll. Occasionally, “Maybe your response is a little slow, your patience is a little short and your attention to detail” is not as sharp. Mistakes “can happen.”

But the rewards outweigh the downside, Cobb says.

“To talk to somebody and give them hope and help to get through (a crisis),” she says. “To be able to give officers information to keep them safe … Just hearing the relief (when she talks a caller through a medical emergency). I really love it. Every single day I make a difference in at least one person’s life.”

Contributing: Daniel J Gross of The Greenville News