HOT SPRINGS, Ark. — The right to a fair trial is one of the founding principles enshrined in the U.S. Constitution. It comes a few amendments down the page in the Bill of Rights from the right of the people to address and question the government.

In an age of social media and fast-moving information, balancing those two rights can be difficult, especially in courtrooms and jury boxes.

Our investigation found that the balance has tipped too far to one side on an Arkansas judicial circuit that covers a county with 100,000 people.

In the Garland County seat of Hot Springs, judges handling adult criminal cases in the 18th East Judicial Circuit have been issuing dozens of gag orders, or "orders against pretrial publicity," on a routine basis at the request of the prosecuting attorney.

These restrictions against parties in a case speaking outside the courtroom are supposed to be rare and carefully deliberated, but our investigation found they are done as a matter of course whenever an arrest or details of a case receive even minor attention from social or local professional media.

The gag orders tend to create information vacuums, and in complicated cases, have led to conspiracy theories and cover-up accusations.

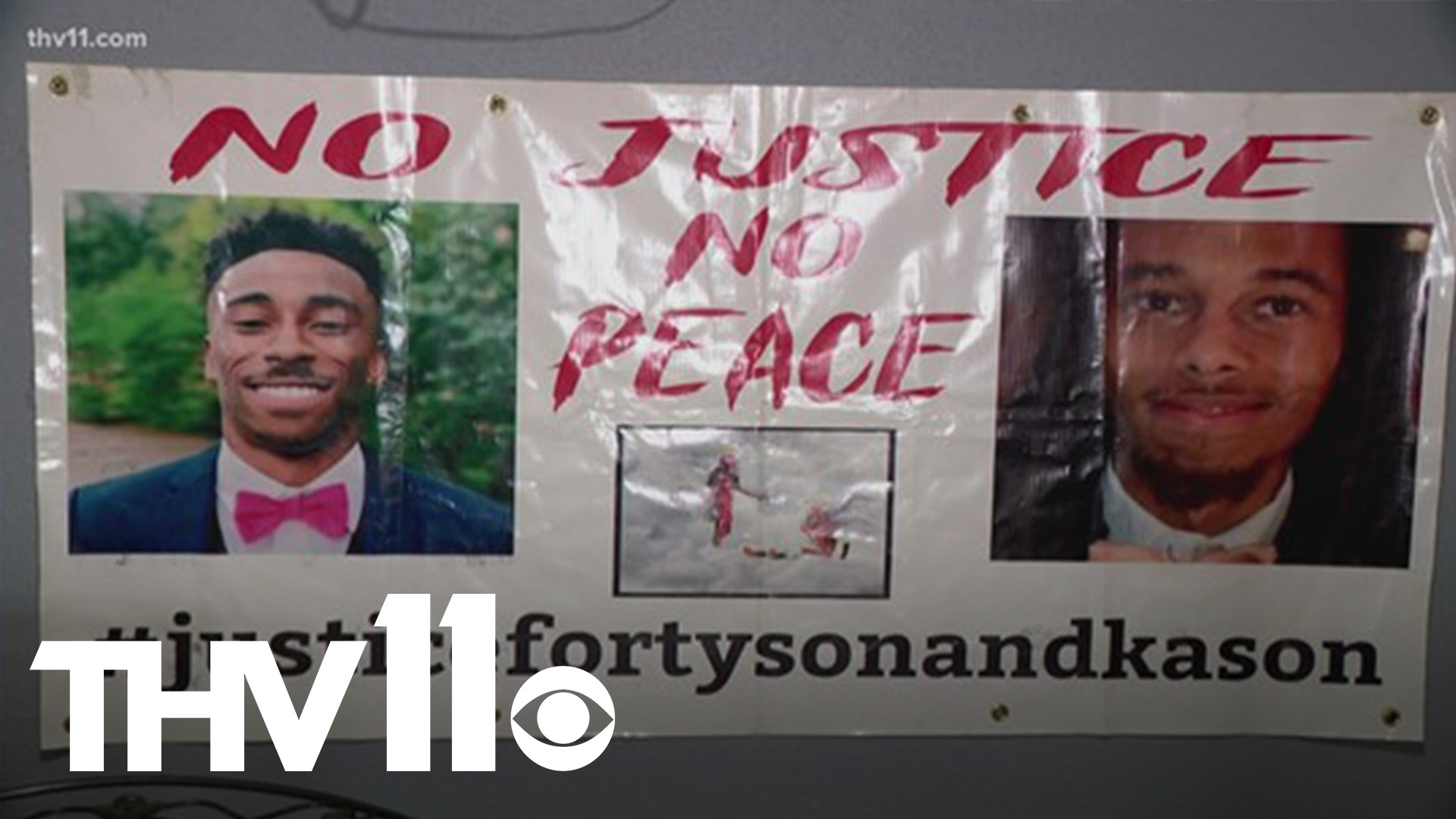

"There's not even words I can use to describe what it does to you. It affects you down to your cellular level," said a grieving Mike Porter, 18 months after two of his sons, Tyson Stewart and Kason Porter, died after allegedly attempting to buy marijuana.

Details of their deaths have never had a public airing in an open court.

In August 2020, the two died when they drove to buy marijuana from Braxton Gravett. When they arrived, a dispute arose. Gravett, who is white, told police Stewart and Porter, who are both Black, tried to rob him, so he shot them and claimed self-defense.

"I think it was just taken as two young Black 'thugs,' kicking in a door and trying to rob somebody," Mike Porter said. "It was just assumed that that was what it was. They couldn't speak on their behalf to say anything different. And the people there that night who were involved, said different."

Gravett was eventually convicted of using a mobile phone to facilitate a drug sale and filing a false police report, according to documents supplied by his attorney, Brent Miller. He received 5-years probation and more serious gun and drug charges were dropped.

The way the justice system arrived at that resolution was hidden from the media, the public, and even the Porters and their supporters, who had clamored for authorities to file homicide charges.

The shooting came amid the summer of unrest over racial justice. With two Black men dead, immediate outrage led to protests, widespread attention on social media and offers by members of the Black Lives Matter movement to come to Hot Springs.

The routine decision to request and grant a gag order in the case starved that spiraling situation of the oxygen of information.

"As a prosecutor, I have an ethical obligation to ensure that the defendant is also entitled to a fair trial and does receive a fair trial," said Michelle Lawrence, the elected prosecuting attorney for the 18th East circuit.

In two decades on the job, including seven as prosecutor, Lawrence said that social media has made holding fair trials very difficult.

"When we would garner 60 people to appear for jury duty, 30 of them would already tell us, 'look, I've already decided' that this individual, most of the time, was guilty," she said.

Lawrence said she believes a gag order fixes that, and so she makes the request to the judge hearing the case. The administrative judge for the circuit, Marcia Hernsberger apparently agrees, and has installed a practice of granting every gag order request.

Judge Hernsberger has not returned any of our numerous calls to discuss the matter.

"What judges have to do, they need to balance the defendant's right to a fair trial, versus the public's right to have information," said John DiPippa, dean emeritus at the University of Arkansas, Little Rock's Bowen School of Law.

DiPippa recognizes the need for gag orders, even though they set up a clash between two parts of the Bill of Rights: the First Amendment and the Sixth Amendment.

"It's not as though it could be done routinely," he said. "In fact, it should be done only in circumstances where it seems likely that information is going to harm the jury pool. And the judge should put on the record what those concerns are."

But gag orders are so routine in Garland County, they go into the record on the same pre-printed form every time.

Of the more than 100 cases we investigated, most involve minors or sex crimes with obvious instances where victims need to be protected. About a third are just notorious cases or notorious defendants.

There's the case of convicted murderer Kevin Duck, who was on the run for a few years after killing his girlfriend and dumping her body in the Ouachita National Forest. Several law enforcement authorities sought the media and the public's help to catch him, but once the court case began, a gag order went in place.

Other gagged cases include a school secretary accused of using district funds for personal use, and an assistant to the then-county judge using public money to buy, among other things, costumes for her dog.

"I don't watch Law and Order or Forensic Files, but I have a lot of friends who do and in mass quantities," Lawrence said. "I think just the type of case generates interest, which generates discussion about it, which generates conclusions without anyone knowing really what the evidence is."

But Lawrence is an outlier when it comes to asking for gag orders.

We looked at Jefferson County and Pine Bluff, a smaller city but with more than two dozen homicides in 2021. No gag orders come up in the public information portal Court Connect.

We found the same thing when we looked in Conway, county seat of Faulkner County.

And in Lonoke County, where the trial of sheriff's deputy Sgt. Mike Davis is drawing international attention for the death of a teenager, no gag orders have been put in place beyond the normal rules of the court. In fact, the judge will move the trial to a larger venue to accommodate the media and public while also protecting potential jurors from hearing protesters outside.

In all four locations, we found no gag orders in the last 5-years using the same search parameters as our query in Garland County.

We also know more cases have since been gagged, but we can't see the actual order because Judge Hernsberger has put an additional barrier in place.

"The clerk in this county and our judges came to a conclusion that none of that stuff would be accessible on Court Connect," said Lawrence.

In other words, the parties can't talk outside court, but the public's main way to find out what happened in court is hidden from view.

DiPippa, the law school dean, and other members of the judiciary that we spoke with said that is a huge concern. It means that while technically the courtroom is open, with the public free to attend proceedings, the schedule of those particular cases is not available for the public to easily find.

And that public includes people like Mike Porter, who technically isn't a party to the case that eventually involved his sons' admitted killer, leaving him in the dark.

"I do not believe that had more attention been drawn to this, that he would have had all of these charges dropped," Porter said. "You have multiple people telling a story this way. And the opposite side of that story...nobody can speak."