LITTLE ROCK, Ark. — As Arkansans continue rebuilding after the devastating March 31 tornado, there's now a focus on what we can learn from the disaster.

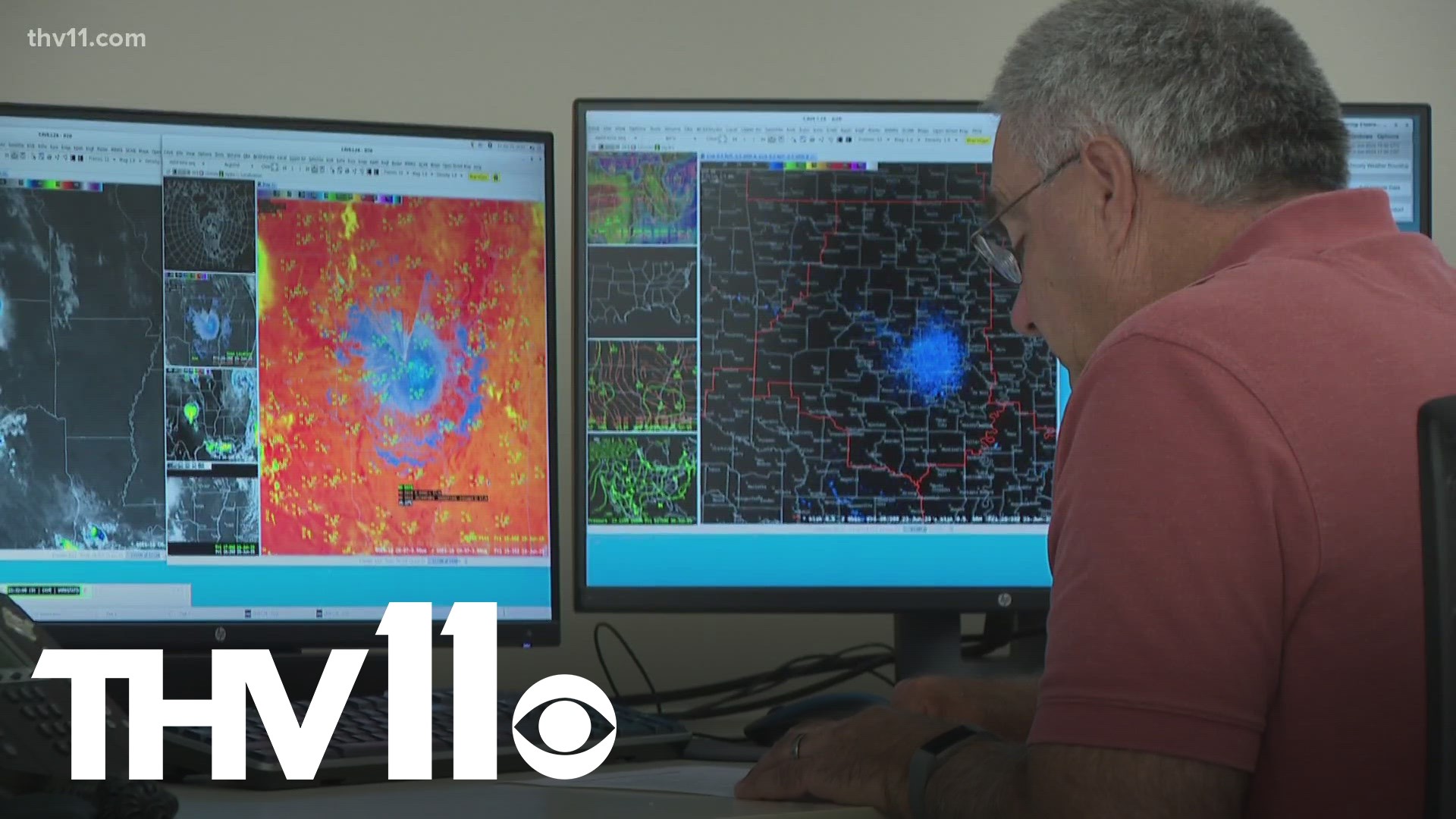

Three months later, as recovery efforts continue, meteorologists like Dylan Cooper and his colleagues at the National Weather Service (NWS) are sifting through thousands of data collected in the storm's aftermath.

Their goal is to learn all they can to save lives when future storms hit.

Cooper said that while the NWS is widely known for its work ahead of storms, like issuing watches and warnings, post-storm research is an equal priority.

“Research is one of the big things we focus on," Cooper said. "To help better understand the events that happened [and] to help better tell the science story.”

The “weather story” Cooper references is one told through data. This story teaches and challenges commonly held misconceptions people have about tornadoes.

Early on in this research, one thing is abundantly clear to these scientists – valleys aren’t a safeguard against tornadoes and don't guarantee protection.

The March 31, 2023, Little Rock tornado dramatically illustrates this.

As the tornado crossed Chenal Parkway, it was an EF1 with estimated 90 miles per hour wind speeds. As the storm began climbing the giant hill up to the Calais Forest Apartments, the storm rapidly intensified into an EF3, packing winds of 140 miles per hour.

It also grew in size to 300 yards wide.

“A lot of this comes down to very complex small-scale factors," Cooper said. "We're talking elevation differences of hundreds of feet, not 1000s of feet."

This hill illustrates the impact that even subtle elevation changes can have.

However, the elevation drop that follows this hill dismantles the belief that valleys offer protection.

In this valley, we find the EF3 tornado damage, where winds are estimated to have reached 165 miles per hour. The official NWS damage assessment classified this area as having the “core of the worst damage.”

Cooper explained the valley's drop in elevation could have enhanced the tornado's strength. He used the example of a figure skater lifting their arms above their head to elongate themselves, increasing speed.

“With what we saw in that specific area, valleys could actually enhance the strength of tornadoes," Cooper said. "That myth was effectively busted. It's a myth that I've heard. I don't know how often you're protected from tornadoes if you live in a valley.”

He's unsure where the myth originated, but the Little Rock tornado busted it.

“I think this case pretty much proves that you're not safer in a valley, unfortunately," Cooper said.

How the tornado made its way through the hills and valleys of west Little Rock isn’t the only thing that caught researchers' attention.

The path also took it across the Arkansas River, dispelling another long-standing belief regarding how these powerful storms behave.

“The tornado was in progress the entire time," Cooper said. "As soon as it got to the other side of the river, it really intensified very rapidly. So, as far as bodies of water preventing tornadoes, it's another myth busted.”

While it’s obvious to some, there’s also a long-held notion that tornadoes can’t hit cities. The events of March 31, 2023, prove otherwise, joining a list of other cities to take direct hits.

Cooper believes this myth is simply a matter of chance.

“It's really just probability and statistics," Cooper said. "As far as just not very much area for that tornado to hit compared to suburbs and rural are.”

Cooper and the National Weather Service will tell you that elevation and terrain are front in center in their ongoing research, though it also includes many other variables.

The moral of the story is preparedness and understanding the unique hazards. As people work to rebuild their lives, the NWS will continue studying the tragic events of that March afternoon.